Lectins

Lectins: Are These Food-Based Proteins Friend or Foe? A controversy

John Watson; Reviewed by Anya Romanowski, MS, RD

August 17, 2018

The seemingly endless search for that one insidious element in our diets, which if eliminated, can restore our waistlines, health, and happiness has uncovered its latest culprit: lectins. If you have never heard of lectins, carbohydrate-binding glycoproteins found in many foods, prepare to get familiar with what some are deeming “the next gluten.”[1]

And as with going gluten-free, there is a slew of information online and elsewhere about the lectin-free diet that experts say has at best a tangential relationship with the scientific evidence.

What follows is a primer on this emerging dietary trend to help you understand whether lectins are friend, foe, or something entirely more interesting.

An Unlikely Antagonist

Lectins are proteins that can be found in most living organisms, and were first discovered in the late 1880s. Certain lectins possess an inherent toxicity thought to have evolved as a natural deterrent to protect plants and animals from being eaten. It appears to be working, because several animal species have been shown to experience reduced intestinal absorption and resulting morbidity after ingesting lectins.[2] Essentially, lectin toxicity mirrors the effect of food poisoning, and serves as an evolutionary caution sign.

But this is in no way true of all lectins, whose range is considerable. Most lectins are inactive with no biological activity, whereas others are thought to have health benefits, and some, such as ricin, can be a deadly poison upon consumption.[3]Putting them all under one umbrella is basically meaningless.

The main case against lectins comes from their biological activity. Lectins strongly and specifically bind to sugars (carbohydrates). This affinity for sugars is captured in the word “lectin” itself, which is derived from the Latin word legere, or “to select.”[4] Lectins have been compared to keys that can unlock specific carbohydrates, which, in turn, can disrupt the cells in which they are housed and cause inflammation.[5]

If you consume certain lectins and do not have the enzymes to properly digest them, they can pass through the digestive tract undisturbed, which has been linked to nutrient deficiencies, disrupted digestion, and severe intestinal damage.[6] There are also proposed risks if lectins enter the body’s circulation. Review articles based mostly on animal findings have posited that ingested lectins could increase intestinal permeability; get past the gut wall; and deposit themselves in distant organs, causing inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes.[7,8]

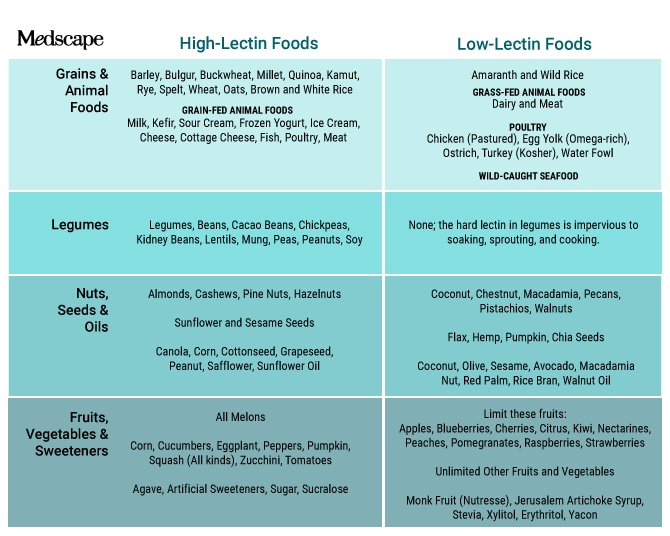

Lectins’ new status as a public health hazard is an unlikely turn of events, because they are found in foods generally considered the staple of a healthy diet—whole grains, beans, peas, tomatoes, nuts, milk, and fruit, to name a few. Lectin-containing foods could double as the shopping list of a health fanatic (Figure). This makes the prospect of avoiding lectins somewhat dubious.

Figure. High- and low-lectin foods.

Debunking the Lectin-Free Diet

Unlike other dietary interventions with hard-to-pin-down origins, the lectin-free diet craze can be sourced to one person: Steven Gundry, MD, a California-based cardiologist and heart surgeon who attributes going lectin-free to his own improved health. Gundry has outlined what he sees as the hazards of lectins in the 2017 book The Plant Paradox: The Hidden Dangers in “Healthy” Foods That Cause Disease and Weight Gain. It advances Gundry’s thesis that the ingestion of lectins incites an inflammatory process that can cause weight gain and serious health conditions, such as autoimmune disease.

Gundry has been pilloried by some for his alarmist language comparing ingested lectins to initiating chemical warfare on your body and for extending his influence into the commercial realm, offering a nutraceutical product called Lectin Shield on his website at nearly $80 a bottle. But the book is nonetheless a best seller, and his narrative about lectins is trickling down through various media outlets and vocal proponents.

Critics argue that the trouble with this is that it doesn’t seem to be backed up with any convincing clinical research, and doesn’t even pass the test of basic logic. As many have pointed out, the global populations with the longest, healthiest lifespans avail themselves of diets rich in lectins, whereas the United States famously does not. They ask quite rightly, if lectins were truly the source of our dietary struggles, shouldn’t we be in better shape from avoiding them in relatively higher proportions than other societies?

Again, it’s important to remember that lectins are far from monolithic and vary in qualities from food to food, from the benign to the toxic.[9] Furthermore, and quite crucially, they are rendered safe for consumption upon cooking. So if you find yourself with a hankering to eat raw kidney beans, you will probably experience some gastric distress; however, if you instead place those same beans in a pot and let it simmer, the prevailing science shows you will be at no risk. That’s because the toxic lectin content in raw red kidney beans drops by 99% after cooking them (from 20,000-70,000 to 200-400 hemagglutinating units).[3]

It is this disconnect between common sense and hype that has led high-profile publications, such as The Atlantic [1] and the Washington Post,[10] to label the lectin-free diet as “pseudoscience” and promoting “insidious misinformation.”

Getting Free of Fads

Going lectin-free appears poised for the life cycle of most dietary fads, with a surge in interest followed by an inevitable fall from grace, when it is supplanted by the next new thing. However, early reactions to lectin-free diets from dietitians and other experts have been fairly adamant that it is a baseless intervention,[1,10-12] which may go some way toward sapping the enthusiasm.

What does enjoy a robust foundation of scientific evidence is the value of consuming a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, fiber, whole grains, and other beneficial foods. Taking these off our plate in pursuit of a diet that many consider a fad would likely lead to an actual health crisis.

And in an interesting twist, the very same properties that are causing lectins to be removed from diets are also making them the source of intense clinical interest. To researchers in the emerging field of lectinology, a strongly binding protein with toxic qualities that can resist digestion, survive gut passage, and remain active within the body does not sound like a cause of fear, but instead something to harness. They are investigating possible uses for a therapeutic lectin compound for treating cancer, HIV, rheumatic heart disease, diabetes, ocular diseases, and more.[9,13,14]

Although these efforts are still in the early stage, if they prove even moderately successful, the day may come when lectins are seen not as detriments to our health, but something that enabled us to fight back against some of the greatest threats to it.

From the editor

(

References

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

- Hamblin J. The next gluten. The Atlantic. April 24, 2017. Source Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Lampel KA, Al-Khaldian S, Cahill SM, eds. Bad Bug Book Handbook of Foodborne Pathogenic Microorganisms and Natural Toxins. Bethesda, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 2012. Source Accessed August 8, 2018.

- These 50 foods are high in lectins: avoidance or not? Superfoodly. October 8, 2017. Source Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Stillwell W. An Introduction to Biological Membranes: Composition, Structure and Function. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science; 2016.

- Sullivan K. The lectin report. June 1, 2018. Source Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Vojdani A. Lectins, agglutinins, and their roles in autoimmune reactivities. Altern Ther Health Med. 2015;21 Suppl 1:46-51.

- Freed DL. Do dietary lectins cause disease? BMJ. 1999;318:1023-1024. Abstract

- De Punder K, Pruimboom L. The dietary intake of wheat and other cereal grains and their role in inflammation. Nutrients. 2013;5:771-787. Abstract

- Lam SK, Ng TB. Lectins: production and practical applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:45-55. Abstract

- Rosenbloom C. Going ‘lectin-free’ is the latest pseudoscience diet fad. Washington Post. July 6, 2017. SourceAccessed August 8, 2018.

- Amidor T. Ask the expert: clearing up lectin misconceptions. Today’s Dietitian. October 2017. Source Accessed August 8, 2018.

- Ware M. Everything you need to know about the lectin-free diet. Medical News Today. October 3, 2017. SourceAccessed August 8, 2018.

- Coulibaly FS, Youan BB. Curre